Disclaimer: The information in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice from SFOX or the individual author, nor is it intended to be a substitute for legal counsel on any subject matter. No reader of this post should act or refrain from acting on the basis of any information included in, or accessible through, this article without seeking the appropriate legal or other professional advice on the particular facts and circumstances at issue from a lawyer licensed in the recipient’s state, country, or other appropriate licensing jurisdiction.

The creation of cryptocurrencies brought in new and unique challenges for regulators. The question of whether cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin could be classified as money, property, commodities, and/or securities sparked legal debates around the world. As regulators raced to understand and legislate the new technology, it continued to advance on its own.

Over $11 billion was raised for cryptocurrency projects via initial coin offerings (ICOs) in 2018, up from $10 billion the year before. However, the nature of these ICOs was hotly debated: Do the tokens that investors buy represent a stake in the crypto project itself? If so, these ICOs may have been selling securities, which, if not properly registered, could leave project teams and investors open to a host of legal problems.

As regulatory authorities continue to make rulings and set precedent for cryptocurrency classifications, the SEC is now working through a backlog of ICOs to determine whether they sold unregistered securities. After years of unclear regulatory guidance with regard to the crypto sector, the SEC is finally establishing the same legal and regulatory clarity for investors that exist in other markets.

To understand the implications that a more active regulatory environment may have on the cryptocurrency ecosystem, we need to take a closer look at what makes a security and how the SEC is deciding which ICOs sold securities. The SEC’s famous Howey Test has been the benchmark for such decisions since the 1940s, and it all started with an ill-fated citrus-grove venture.

The Howey Test

Back in 1946, the W.J. Howey Company leased out some of its Florida farmland to “finance an additional development.” The people buying land from the Howey venture were speculative investors aiming to see a return generated from the efforts of the citrus farmers.

This raised concerns with the SEC over whether or not the land itself could be seen as a security, leading to a landmark lawsuit. This would decide whether the Howey Company would be allowed to continue selling the land and whether any plots that were already sold had been sold legally.

The lawsuit was based on the fact that investors weren’t simply hoping to see profits from an increase in the land’s value. They were effectively buying into a farming operation to share in the profits, but the W.J. Howey Company never filed for the right to sell shares or securities. The Supreme Court stated that “the transactions in this case clearly involve investment contracts, as so defined. The respondent companies are offering something more than fee simple interests in land . . . they are offering an opportunity to contribute money and to share in the profits of a large citrus fruit enterprise.”

W.J. Howey was found to be in breach of US securities law, and the landmark case set a precedent on which future rulings would be based. Following the case, the SEC devised a “Howey Test” as a means of determining whether an offering counted as a security. There are four criteria that, according to the test, a security offering satisfies:

- The offering involves a monetary investment.

- There is an expectation of profits from the investment.

- The investment is in a common enterprise.

- Any profit comes from the efforts of a promoter or third party.

A similar debate has been playing out in crypto over the last couple of years. The issue of whether the citrus-grove contracts represented a stake in the W.J. Howey business itself, an investment contract of sorts, is echoed in the many ICOs that have sold tokens to raise money for their own projects. Do these tokens represent investment contracts? How can the SEC regulate ICOs without stifling growth and innovation in the crypto space?

Applying the Securities Debate to Crypto

From 2013 onward, initial coin offerings raised billions of dollars. The invention of Bitcoin, a type of digital cash stored on a network that nobody controls, paved the way for new projects to raise money.

Cryptocurrency and blockchain projects raised funds by accepting investments, with investors hoping to see a return on their funds. Typically, an ICO investor transferred a well-known cryptocurrency like BTC and, in return, received ICO tokens: native cryptocurrency tokens specifically designed to raise money for a project. Given the lack of clarity over whether the cryptocurrency investments were legally monetary in nature, it was difficult to say whether ICOs were selling securities or not.

Muddying the waters further, many projects framed their offering as “utility tokens.” According to these projects, the coins they were selling to investors had a key function in the performance of their project, rather than being a purely speculative investment. The investments were made in crypto, not money, and a rise in the value of the coin was not a direct reflection of the success in their project.

The SEC made statements indicating that these projects may, in fact, constitute security offerings despite the utility token framework. This could have a major impact on the space: any projects found to be selling securities could be liable for prosecution and subject to retroactive legal action pending upcoming legislation. In fact, as of 2019, this has already begun to happen, leaving investors and projects scrambling to figure out whether they’re affected. Of course, regulation also brings with it legal protection for investors.

A 2018 study by the Wall Street Journal found that one in five ICOs showed “red flags” of fraud. Due to the prevalence of such fraud, the SEC decided to release a tongue-in-cheek warning and educational guide. The regulatory body published a site offering to sell HoweyCoins, a fake ICO site containing the common hallmarks of fraud. Investors clicking the “buy coins” link were instead directed to an SEC page to educate readers on fraud.

With much of Bitcoin’s white paper striking a tone against regulation, some participants in the crypto space may be inclined to push back on government involvement. However, the ICO fraud statistics and the SEC response are reminders that some regulation can be a good thing for the space, protecting investors and helping legitimate projects to thrive. We’re going to take a look at some of the well-known examples of regulatory scrutiny around cryptocurrency projects and whether or not those projects meet the criteria enumerated in the Howey Test.

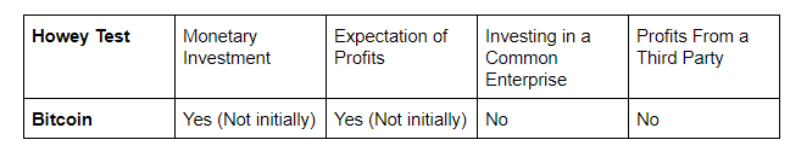

Bitcoin

As the original cryptocurrency, Bitcoin is a bit of a special case. There was never an investment of money required from retail investors to kickstart the Bitcoin project. Initially, the coins were minted and distributed to miners, and a secondary market for them subsequently emerged.

Investors weren’t necessarily expecting to profit from these bitcoins at first, with many early investors simply being interested in the concept of peer-to-peer digital cash. Bitcoin’s creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, is an unknown individual or group, making it impossible to file an injunction against them. Furthermore, because the creator doesn’t control the decentralized network, there is no common enterprise. All told, this means that Bitcoin does not meet the criteria of a security — and, in 2019, this was put to the test.

In mid-2019, a company called Cipher Technologies Bitcoin Fund filed to register with the SEC as a closed-end interval fund and investment company. Cipher asserted that Bitcoin was a security in this filing, but the SEC ruled on October 1, 2019, that Bitcoin is not a security, saying:

Among other things, we do not believe that current purchasers of bitcoin are relying on the essential managerial and entrepreneurial efforts of others to produce a profit.

This ruling set a precedent that will impact future rulings on other cryptocurrency projects. Because Bitcoin is decentralized and not dependent on the efforts of a structured hierarchy, it does not constitute a security.

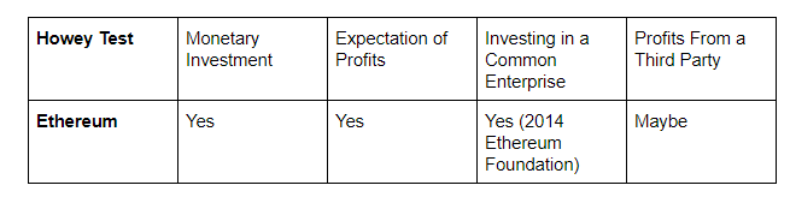

Ethereum

The regulatory path for Ethereum is less clear for a number of reasons. Unlike Bitcoin, Ethereum raised funds via an ICO in 2014, led by a core team of developers as part of the Ethereum Foundation. While SEC chair Jay Clayton stated, “I believe that every ICO I have seen is a security,” he also appeared unwilling to lump Ethereum in with other ICOs, saying, “When you depart from the bitcoin or the ethereum and you get into the tokens, the hallmarks become pretty clear.”

The SEC has yet to make a final ruling, but it seems that it does not consider Ethereum to be a security. SEC staff member William Hinman said, “Based on my understanding of the present state of ether, the Ethereum network, and its decentralized structure, current offers and sales of ether are not securities transactions.”

By applying the Howey Test, the SEC found that Ethereum is now decentralized to the extent that the third-party profits category does not apply, nor does Ethereum represent a common enterprise, making the network and ether tokens free from securities classification.

Hinman was careful to clarify that Ethereum does not currently classify as a security. However, whether this applies to the original ICO Ethereum launched in 2014 is unclear. Interestingly, a separate US regulator has its own take on Ethereum, claiming that it classifies as a commodity.

The CFTC has stated that Ethereum is most likely a commodity, not a security, but that proof-of-stake (PoS) networks like Ethereum 2.0 could be considered securities. The PoS method of consensus validates transactions and creates blocks by granting validation rights to stakeholders with large sums of funds, which could constitute a common enterprise and a monetary investment.

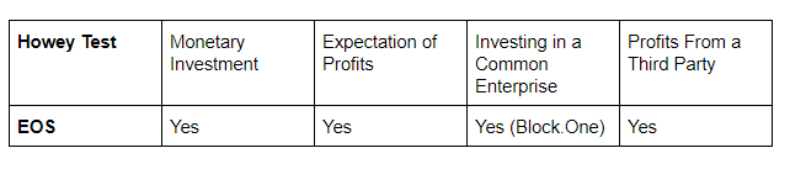

EOS

EOS raised $4.1 billion in a record-breaking ICO between 2017 and 2018. The SEC found that the ERC-20 tokens used to raise funds in the ICO classified as securities, meeting all four criteria of the Howey Test, and filed an injunction against Block.one, the company behind EOS. EOS was ordered to pay $24 million in fines.

An SEC press release pointed out that while the yearlong ICO began before it published regulatory guidelines in its DAO report relevant to ICOs, the fundraising continued after publication. Block.one also didn’t file for securities exemption. A Block.one press release stated, “The SEC has simultaneously granted Block.one an important waiver so that Block.one will not be subject to certain ongoing restrictions that would usually apply with settlements of this type. Block.one believes the SEC’s granting of this waiver evidences Block.one’s continuing commitment to compliance and best practices in the United States and globally.”

It’s worth noting that the ruling applies only to the initial ERC-20 tokens distributed in the ICO, not to EOS tokens themselves. EOS tokens that are now in circulation are considered to be an independent currency on a decentralized system, as opposed to the ICO tokens created purely to raise funds and offer investment opportunities.

While Block.one was hit with a fine by the SEC, that fine amounted to 0.58% of the total amount raised. As the largest company to have failed the Howey Test and received an injunction, Block.one faced relatively mild consequences. However, the SEC press release seems to indicate that companies launching ICOs after the DAO report without registering as security offerings may be dealt with more harshly.

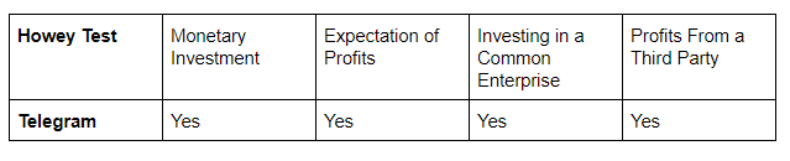

Telegram

Telegram’s parent company, TON, launched the second-largest ICO after EOS in 2018, raising $1.7 billion. The SEC filed a legal complaint against the encrypted messaging application company, stating that both Telegram and TON had sold unregistered securities. TON stated that Grams, the crypto token that was sold, is a utility token rather than a security. The SEC denied this claim for a number of reasons.

First, the blockchain that Grams tokens are designed for did not yet exist at the time of the ICO, making the investment a speculative one. Second, according to the SEC, there is still no concrete use for Grams tokens at this time:

The TON “ecosystem” did not exist and does not exist today. There are not now and have never been any products or services that can be purchased with Grams.

Telegram’s ICO was open to accredited investors only, rather than the general public. This impacted the ruling: it was seen as unlikely that all of the investors were interested in Grams’ utility and was seen as more plausible that they sought to profit from a speculative investment in the success of the Telegram venture. With the TON network due to launch, the issue became more pressing. TON aimed to distribute Grams to the general public via the blockchain network, potentially exposing retail investors to the risk of buying unregistered securities. The SEC halted the sale in October 2019.

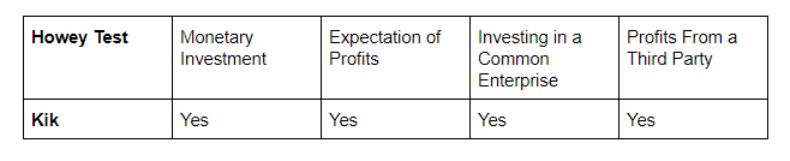

Kik

Kik, another popular messaging app, raised $100 million in a 2017 Kin token ICO that was recently ruled an illegal capital raise after the SEC took the matter to court in September 2019. The SEC alleged that Kik was running out of money in 2017 and described the ICO as a “Hail Mary” attempt to raise more funds, skirting investor protection laws in the process. Kik announced that its messaging app, which boasted almost 10 million monthly users in 2018, would shut down. Crypto subsidiary company Kin laid off 70 staff members following the ruling.

Interestingly, it didn’t stop there. Kik’s CEO, Ted Livingston, stated that while the app was dead, the company would now focus its efforts on the Kin token ecosystem instead, taking a stance against the SEC. Livingston said:

Becoming a security would kill the usability of any cryptocurrency and set a dangerous precedent for the industry. So with the SEC working to characterize almost all cryptocurrencies as securities we made the decision to step forward and fight.

Livingston went on to say that the Kin currency is used by “millions of people in dozens of independent apps” and asserted that it would not be so easy to shut down. This is a bold statement to make because the SEC is convinced that Kin tokens are unregistered securities as well. Livingston claims that because Kin is not widely available on many exchanges, it does not constitute a speculative asset, a claim unlikely to sway the regulatory body. With the Kin Foundation seemingly squaring up against the SEC on the ruling, this case will prove to be an interesting study of how the government deals with a noncompliant cryptocurrency project refusing to shut its doors.

Regulating Crypto

The SEC has also filed against many smaller projects for breaching securities laws that were found to be selling securities. Two startups, Paragon Coin Inc. and Airfox, were fined $250,000 each. The firms were not charged with fraud but instead offered a deal in which they would bring their ICO under SEC oversight and offer refunds to investors. While the goal of the ruling was to protect investors by allowing them the option to reclaim funds, both companies have missed their deadlines to pay back investors.

The results of cases like these will ultimately feed into the way the SEC handles future rulings. The degree to which noncompliant ICOs and their associated projects will be penalized is currently being decided. Already, SEC representatives have voiced concerns that such lenient rulings are impractical because the money to repay investors may have been spent or moved, and this may lead to harsher rulings in the future.

While many projects may face litigation, it’s difficult to express nostalgia for the days before ICO regulation. With 20% of all token raises being identified as potentially fraudulent, and many more simply raising funds without creating a viable product or solution, perhaps the involvement of the SEC in cryptocurrency fundraising will end up leading to more valuable innovations and a safer climate for investors supporting the industry.

The above references an opinion and is for informational purposes only. It is not intended as and does not constitute investment advice, and is not an offer to buy or sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any cryptocurrency, security, product, service or investment. Seek a duly licensed professional for investment advice. The information provided here or in any communication containing a link to this site is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject SFOX, Inc. or its affiliates to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. Neither the information, nor any opinion contained in this site constitutes a solicitation or offer by SFOX, Inc. or its affiliates to buy or sell any cryptocurrencies, securities, futures, options or other financial instruments or provide any investment advice or service.